Shallow socializing, crush, and dāzi (搭子) are all trending key words when it comes to relationships on Xiaohongshu this year. On social media platforms, young people are creating groups for finding dazi — companions who share common interests and participate in activities together — looking to find some temporary companionship as they engage in hobbies, travel, or even get through daily chores like grocery shopping.

Unlike close friends, who socialize frequently and keep in close contact, a dazi is a more temporary and sometimes superficial social partner.

To understand the appeal and implications of dazi culture, I spoke with Gen Z users on Xiaohongshu, group leaders, and active dazi seekers who’ve embraced this trend in their daily lives. Here’s what they shared about how dazi culture has transformed their social lives and shaped their views on modern relationships:

“Female born in 2000 is looking for an outgoing, straightforward conversation dazi,” a post on Xiaohongshu reads. “Vulnerable people and easily irritated people please stay away.”

A search for “dazi” on China’s lifestyle-focused social media platform Xiaohongshu, or other social networks such as WeChat and Douyin, will turn up posts by numerous users seeking various types of companions like food lovers, fitness fanatics, travel buddies, weekend hikers, or study companions.

The term “dazi” comes from Shanghai dialect and originally referred to “card-playing buddies.” Later, the term developed a broader meaning, simply referring to companions who participate in activities together.

Besides making public posts inviting dazi to join them for activities, people can also find dazi through groups hosted on the same social networks. The level of organization within groups varies. In many cases, group founders take on a leading role, managing the logistics of events or activities. For example, a group leader might specify a meeting time, establish group rules, and facilitate communication. However, many dazi groups operate democratically, allowing members to contribute equally. The flexibility is part of what makes dazi culture appealing — it accommodates spontaneity while fostering a sense of belonging.

Refreshing and uncomplicated

Anna Li, a 24-year-old who frequently uses Xiaohongshu to find hiking companions, describes her dazi relationships as “refreshing” and “uncomplicated.” “In dazi groups, there’s no pressure to overshare or get too personal,” she explains. “We’re just here to have fun and hike together, and if our schedules don’t align one weekend, that’s totally okay.”

Unlike traditional friendships, which might have been formed over a long period of time in school or at work, dazi don’t have any limit when it comes to age or geographical location, nor a sense of social obligation. This new type of relationship prioritizes freedom, comfort, and enjoyment over commitment.

“My close friends don’t ski and those who ski already have families,” says Ting Cui, a 29-year-old living in Shenyang, “So I take the occasion to make dazi relationships through skiing.” For Ting, these relationships act as a social safety net, allowing her to share experiences without the traditional expectations of friendships.

One appeal of dazi culture is its ability to help young people fill social gaps without the demands of long term, emotionally-binding friendships. In a fast-paced, often transient digital world, this approach to socializing offers an alternative to traditional friendships that may no longer fit with modern lifestyles.

“Everyone’s busy”

“Everyone’s busy, and not all friendships last,” says Jie, a Xiaohongshu user who often joins dazi groups for weekend getaways. “Dazi groups help me do things I enjoy without the need for long-term commitment. If I move away or find a new job, I don’t have to worry about disappointing anyone or losing touch.”

For many, dazi culture provides a way to enjoy a supportive environment that is task-oriented, allowing them to feel socially connected while maintaining personal boundaries. It’s a form of shallow social interaction that, paradoxically, meets deeper needs by respecting individual independence.

“Dazis around me are practical. For example, I used to hire a fitness coach, but it is quite expensive,” one lifestyle influencer on Xiaohongshu commented in a vlog post, discussing the role of dazi with a fellow influencer. “However, when I started to train with a fitness dazi, we motivated each other and set goals to achieve together. Now I no longer need a coach,” he added.

“The relationship is purpose driven, once the purpose fulfilled, we are no longer bound together,” he further elaborated. “Dazi relationships rely on current needs to exist. Once the need is satisfied, the relationship naturally ends.”

According to a report published in 2023, more than 60% of young people in China are actively developing dazi relationships, while 90% of young people are aware of the concept.

Among careers where dazi use is the most widespread, civil servant tops the list, with the report stating that 60% of civil servant respondents participated in the practice. In contrast, only 28% of freelancers frequently searched for a dazi.

Interestingly, dazi culture isn’t just about convenience or fun — it also serves as a form of self-care. Many young people see these relationships as a way to keep their social batteries full without the stress that often accompanies deeper friendships. In this sense, dazi relationships become a tool for maintaining mental wellbeing.

Grace Wang, a Gen Z skier who leads a skiing dazi group on Xiaohongshu, explains, “As a leader, I see how many people benefit from having casual social outlets where they can enjoy skiing without any strings attached. Many of them have expressed how it helps with mental health, as they don’t feel pressured to be available or involved outside the group activities.”

Conserving emotional energy

In a world where social pressures are high, especially online, Gen Z values forms of connection that respect boundaries. In general, they seek to protect their emotional energy by engaging in low-risk, flexible relationships.

This form of compartmentalization appeals to many in a generation that is deeply conscious of the toll social obligations can take on mental health. Anna pointed out that in her experience, “Most of my friends are supportive of dazi relationships because they feel it respects everyone’s time and mental space. We’re not less close; we’re just more selective with how and when we spend time together.”

Zoe Zhao, an assistant professor of sociology at UC Santa Cruz, explained to RADII that Gen Z’s preference for dazi aligns with broader changes in how this generation perceives relationships.

“Younger people value autonomy and prioritize their mental health. Dazi allows them to engage socially without being weighed down by obligations,” she said. “It reflects a changing societal view on friendship, where connections are flexible and purpose-driven rather than emotionally intensive.”

However, dazi relationships still remain controversial for their disposable nature.

Over the past few months, posts have started to appear on Xiaohongshu complaining about how this “no strings attached” approach to relationships has left many feeling hollow and like they’ve been treated as an object.

“I wanted to make friends with a girl I go to movies with, but she said that she has dazi for other activities,” a Xiaohongshu user lamented in one post, “I feel like a tool to satisfy her need in one specific field without any possibility of further emotional investment.”

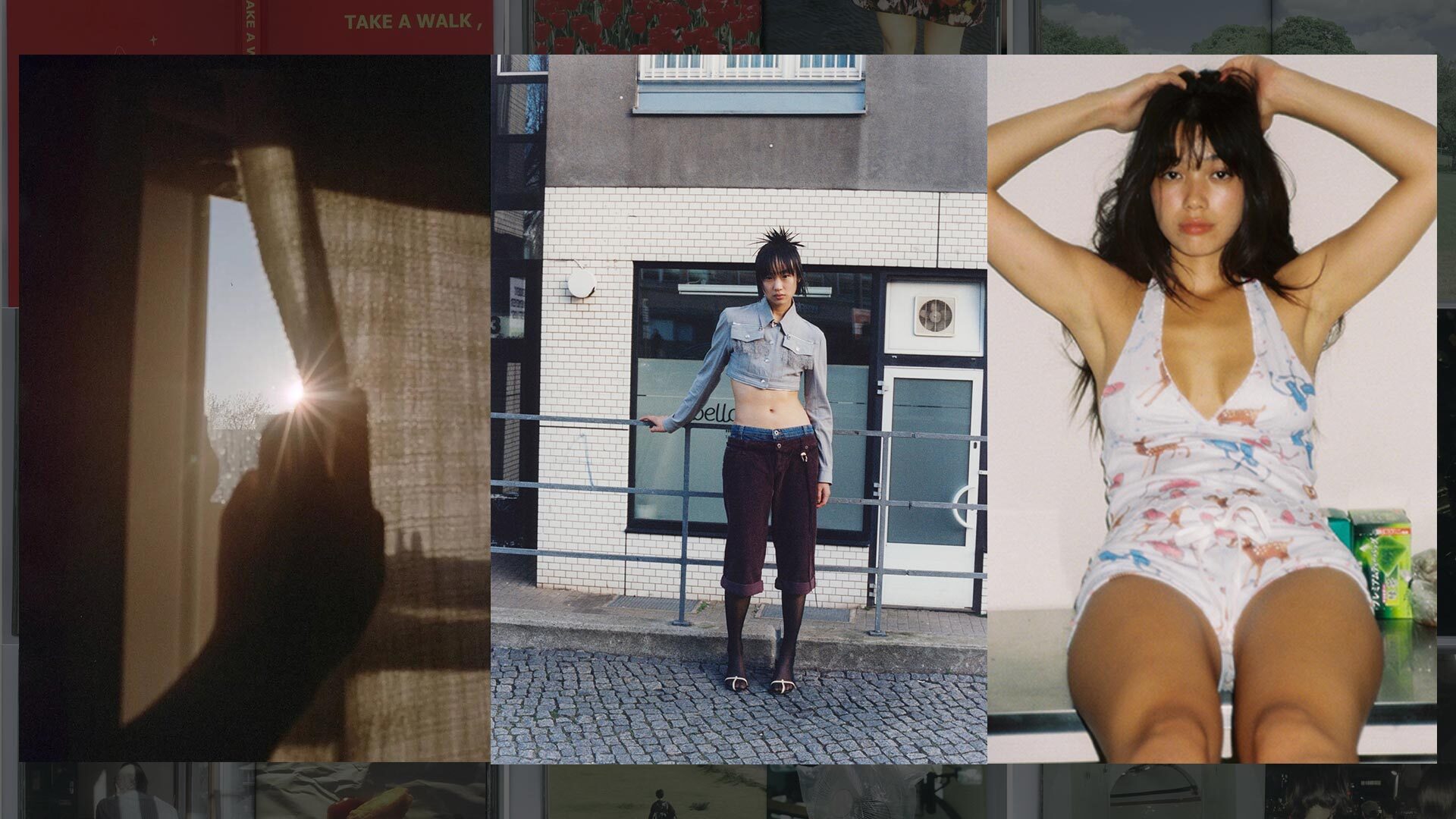

Illustrations by Haedi Yue.